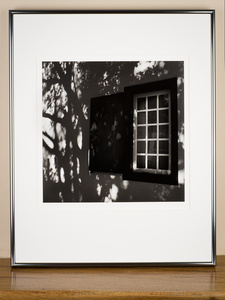

A framed, matted, and dry-mounted print. It is missing my signature in the lower-right corner of the opening, because this is a work-in-progress print (the blacks are too deep for my liking).

Perhaps I am old-fashioned, but I think a physical print, something tangible, that you can put on a wall, gift to someone, handle, or just share with friends, is a more powerful form of visual art than an ephemeral digital file, or a slide show. There is absolutely nothing wrong, inferior, or superior about digital photography, and I enjoy it very much. With traditional, analogue photography, the primary way to share a photograph has always been a print. I admire digital even more, when it has been printed and presented well. However, I feel that the art of simple, understated print presentation is getting lost in the sea of gigantic prints, affixed to oddest surfaces, rarely adding to the expressive power of an image. I prefer the important detail of a print to be in front of me, rather than stretched onto the sides, or even the backs, of a frame…

Not all traditional prints were equal. For hundred thousands of those made by 1‑hour photo labs there were just a few lovely ones, often those slowly made by hand. While today’s digital photographs seem better than the 1‑hour photo ones, I don’t think we have yet anything that exceeds the quality, and the sensual presence, of a hand-made, silver-gelatin, black-and-white print. I guess I am biased.

A well-made silver-gelatin print has a subtly three-dimensional feel, even though it is not a 3D creation. It it luscious, with juicy, deep blacks, that just have a hint of a tone. I like the faintest hint of a chocolate-plum, which selenium toning offers for my present choice of paper. Unless really warranted, it is not a flat graphite black, or a dull grey, or even, goodness forbid, that greenish blue that looks different in different lighting, or from different viewing angles, that many inkjets produce. I believe today’s digital inkjet (aka giclée) printing benefits the more forgiving, full, saturated colour output, than the subtler black-and-white, where precision is paramount.

A fine print has all the tones it needs, with their contrast, especially in the middle values, under the control of the printer (a person). It does not look real, but it looks the way the spirit of the object, or of the place, that it portrays, seemed to the photographer. Unless heavily manipulated to look artificial, digital pictures can easily look too realistic, and perhaps that is one of the reasons why some digital prints benefit from an addition of artificial grain, texture, or the very popular vignette — side-effects, sometimes unwanted, of traditional photography.

When I walk past a fine print, it brings a smile to my face. It feels like an affordable treasure.

I feel passionate about fine prints. I am on a personal quest to reach that 0.0001% level of rare excellence in traditional printmaking, and I realise the road ahead of me is a long one. At present, to get a reasonable work print (not a fine one), it takes me about 3 – 4 days of work in the darkroom. I like to mount it, overmat it, and place it in a temporary frame (see pictures on the right) and I put it in my house, so that I try to live with it for a while, perhaps for a few weeks. If it still manages to impress, and it looks good, then I am ready to go back to the darkroom to improve it, based on the notes, and the feelings, that I have collected over the weeks it sat on my mantlepiece. For example, the print you see above, did not pass the tests, the deep-black window area needed lightening. A few weeks later, and some 4 – 5 days of darkroom work, I emerge with a couple, maybe six prints, which I hope represent the finest, at this stage of my photographic development. Unfortunately, as I keep learning, and working on my craft, a time comes when I no longer think my older prints were fine enough, and I decide to reprint them again… Indeed, this is exactly what I am currently doing with some of the (Be)Longing landscapes which I exhibited last year. I am adding more tonality to them, lessening some contrasts, and generally making them subtler — I hope.

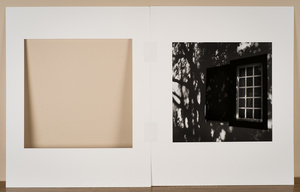

Unframed print, with a bevel-cut overmat, mounted. This is the form in which I prefer to sell my prints, so they only need to be framed by the buyer.

I yet have to see a better form of print presentation than the time-tested, simple approach of dry-mounting it to a 4‑ply (1.5 mm) acid-free, museum-quality neutral-white mount board. Dry mounting is a bit of a craft in itself, requiring some skill, and a bit of luck. It uses heat, delivered by a press, to bind a trimmed print to the mount board, by means of a dry-mounting tissue, a stable adhesive that melts in the press. All the masters of photography used this technique decades ago, and it seems to be the most archival, with the disadvantage — to some — of being rather permanent: once mounted, the print cannot be removed from the mountboard easily. That suits me, as I feel the print with the mountboard should be an inseparable couple, designed and destined for each other, unless the buyer has made alternative presentation arrangements. The mount makes the print perfectly flat and pristine looking, while giving it a pre-measured amount of breathing space around it.

Overmat is attached to the mountboard with acid-free, gummed linen tape, keeping the package together.

To finish a mounted print, I like to mat it with a bevel-cut (angled) opening window mat, cut from the same stock as the mount board. The window is slightly larger than the print, so it is possible to see the entire photograph, with no edges lost — some refer to this approach as floating a window with a well around the print. Striving for a perfect opening with no overcuts, I have only recently started cutting my own overmats. It can still frustrate me on occasion, but the presentation is amazing, when it comes together. The overmat is attached to the mountboard with an acid-free, archival gummed linen tape, keeping the two together, ready for me to sign the overmat, just under the print, and stamp it on the back. All that remains is to frame it, and to put it under a good glass, or acrylic, for additional protection. I prefer to leave the framing to the buyer, as it is personal, and it needs to match the location, but I am happy to recommend simple, aluminium profiles, when in doubt, such as Nielsen profile 3, in colours 10 or 154.

So what is left at the end of the process? A pleasing, joy-bringing, hand-made object, that has an expressive, luminous quality, and a very special presence, wherever its home may be. It is a happy print, lucky in a way, as it made it into the real world, born out of a film negative, and even luckier than the billions of virtual, digital ones, which might only get an occasional glimpse, but which are confined to a life of never being touched, or seen, even from the very moment they have been taken.

I wish your photographs have a chance to live a full life.

4 Responses to It's All About the Print